The knowledge, working methods and tools offered in this element can be used by researchers at their own discretion for one or more of the objectives below:

- Determining which (research) activities to deploy

- Determining the order in which the set objectives and related activities are planned;

- Collectively determining who will be involved in which research activity during the execution phase of the study, with all participants of the partnership

Required preliminary work by the project leader and process manager

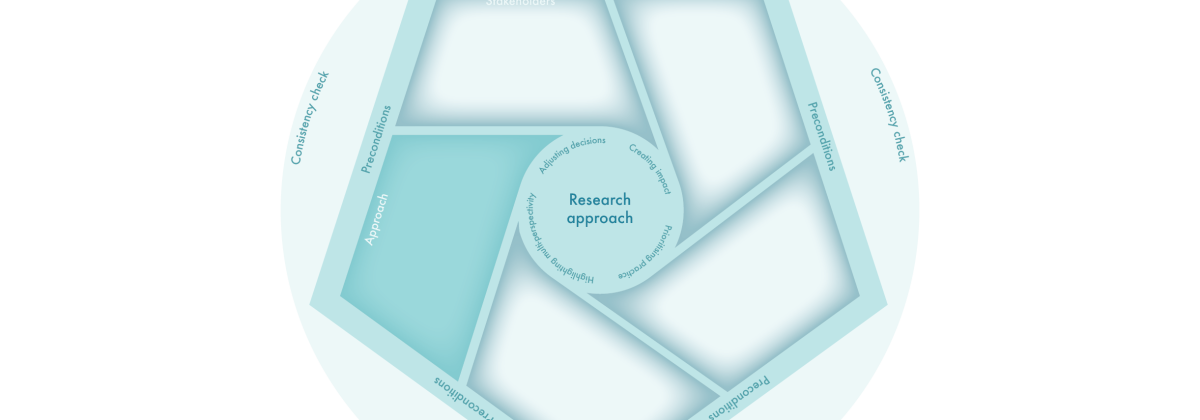

This element is based on the Research Pathway Model (Van Beest et al., 2021; Van Beest, 2023). Based on this element, you can get an overview of how the activities formulated can contribute to the ultimate research objective. This forms the basis of the research approach.

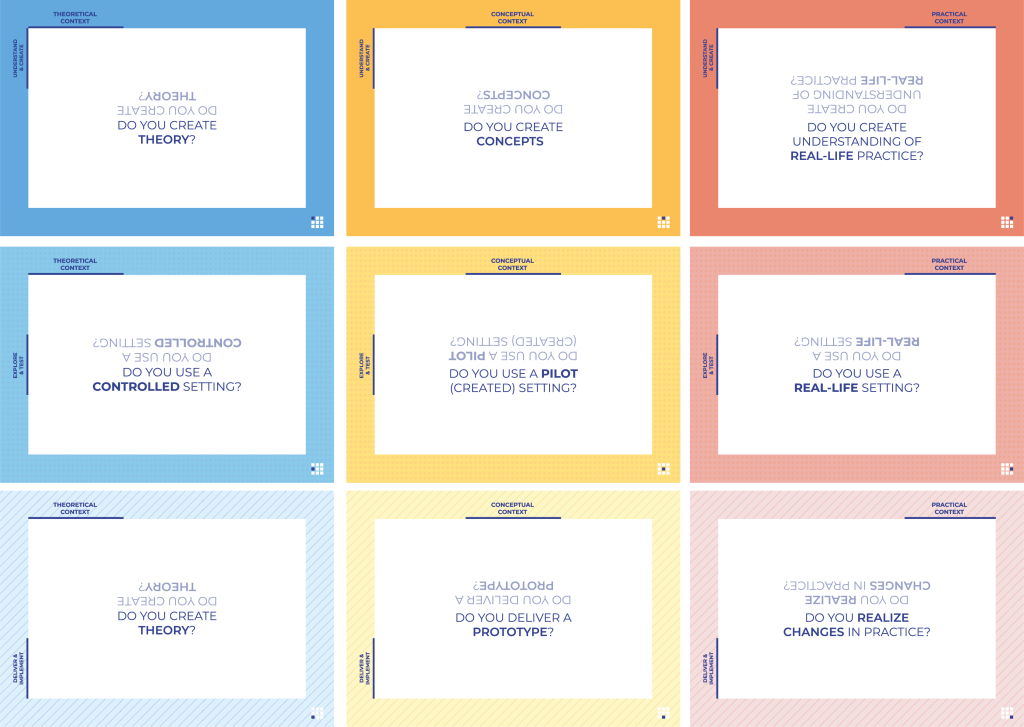

The Research Pathway Model (RPM) is a process model that makes explicit the different steps that can be taken in a research project. This helps to create a better shared understanding of a research project. The model consists of two axes (research contexts horizontally, and research activities vertically) and nine research steps:

The Research Pathway Model distinguishes between three types of research contexts:

1.The theoretical context

In the theoretical context, the process steps focus on ‘creating’, ‘exploring’ and ‘delivering’ a better understanding of problems and where related solutions can be sought.

2.The conceptual context

The conceptual context translates presupposed solutions into a more specific prototype or concept that is created, researched and delivered to third parties, or towards follow-up research. In this context, researchers, students and practitioners translate theory or a practice problem into a prototype. They do this themselves, together with the consortium and with or without the end users, but always in a protected context such as a brainstorming space or a pilot environment.

3.The practice context

The practice context refers to the context in which end users’ practice and/or living environment is explored from the inside, in which a prototype is used and tested, and in which implementation takes place.

The researcher can use the Research Pathway Model to work with stakeholders to determine which steps should be taken in the research project to achieve the set objectives. In doing so, the nine steps of the Research Pathway Model do not necessarily all have to be taken, nor is there any preferred order in going through the steps. This all depends on the objectives of the study.

Tips for project leaders and process managers

- Continue to involve stakeholders in practice and external researchers from the partnership in the development of the research approach:

-

- Remember to keep stakeholders in practice and external researchers involved even during the writing process

-

- Get stakeholders in practice and external researchers to look critically at the chosen methodology.

-

- In the ‘CAYR as a complete 10-step process’ manual provides a complete workshop on this matter called ‘Research Approach’, described on page 36. This workshop combines different working methods to support the partnership participants in providing feedback and input on a draft research design created by a number of researchers within the partnership. The workshop is a half-day session and can be organised either online or on-site. The description of this workshop can give project leaders and process managers more insight into how the working forms and tools listed on this webpage can be used (in combination or not) and can serve as inspiration for how meetings can be organised from the basic principles of CAYR.

- Implement information retrieved during the development of the research approach immediately in the draft of any grant or subsidy application to avoid having to do all the application drafting at the end of the process.

- Sometimes, none of the researchers or stakeholders in practice in a partnership turn out to have sufficient methodological knowledge to properly shape the desired research approach. In that case, enlist the expertise of someone from outside the partnership and have them review of the methodology of the draft proposal. In that case, also consider adding someone with this expertise to the partnership for the execution phase of the study.

Helpful working methods

Choose the context

Working form to jointly discuss what kind of environment someone feels at home in during a project and what this means for the role and approach to be chosen.

Plan the pathway

Working form to jointly determine which research steps will be carried out and what helpful methods can be used within these research steps.

From objective to action

Working form to translate the impact objectives into concrete activities for during the study.

Happy, or questions?

Working form to collectively determine what the research proposal will look like and to possibly outline the intervention that will be developed.

Circling around the approach

Working form to collectively determine what the research proposal will look like and to possibly outline the intervention that will be developed.

Weaving a network

Working method to jointly identify who wants to play what role in the execution phase of the research project and to identify dependencies.

Background information

A research design combines the research approach, the design approach, the didactic approach and the change approach into an integrated design. There are several examples of research designs in which this is the case.

Action research

Action research can be seen as a form of social science research in which both knowledge is developed and practices are improved in a way that stakeholders learn from (Pluut, 2018; Van Lieshout et al., 2017). In this way, action research has a combined approach: a research approach, a change approach and a didactic approach.

Design-oriented research

Design-oriented research is a form of social science research that combines a knowledge objective and a design objective (Van Aken & Andriessen, 2011). During research, a prototype of a solution to a practical problem is developed and this solution is tested a number of times in different contexts. The objective is to develop actionable knowledge, gathering evidence on 1) whether the solution works, 2) under what circumstances it does and does not work, 3) what the mechanisms that make it work are, and 4) in what way the solution can be made context-specific.

A mixed-methods approach is a term often used for studies that combine both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods (Creswell, 2010). This is done in increasingly more disciplines (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2010) because it is appealing for researchers to balance the strengths of both types of research. However, mixed-methods are limited to the research approach and are thus primarily aimed at achieving the knowledge objective. To contribute to the design objective, change objective and professionalisation objective at the same time in a research project, more than a mixed-methods research approach is needed and a design approach, didactic approach and change approach should be added. Each of the four types of research objectives thus requires its own approach.

Research approach

The research approach consists of the research design and research methods for data collection and data analysis. There are many possible research designs and there are similarly many classifications. For social science research, for example, Bryman (2012) distinguishes between:

- Experiments (randomised, quasi-experiment and natural)

- Cross-sectional studies

- Longitudinal studies

- Case studies

- Multiple-case (multi-case) studies

Within qualitative research, other classifications again exist. For example, Letts et al. (2007) distinguish between:

- Phenomenology

- Ethnography

- Grounded theory

- Participatory action research

- Other designs

Of course, research methods also come in many shapes and sizes ranging from surveys to participatory observation. Information on this can be found in the methodology literature published within different fields.

In the CAYR methodology, the importance of distinguishing between research design and research methods is emphasised.

Research design

The research design reflects the way methods are combined to answer the research question. The right combination of methods makes a research approach appropriate. Many different data collection methods can be used within a research design (e.g. a multiple case study). But the answer to the question comes about by comparing the data on the individual cases in multiple ways between them (cross-case analysis). A research design is sometimes (but not always) also linked to specific paradigmatic assumptions: views on how the world works, what knowledge is, as well as ethical and methodological assumptions (Lincoln & Guba, 2000).

Research methods

Research methods themselves do not provide information on how a question is answered, only on how the data are collected and analysed. When a research design fails to describe the way research methods are configured into a research approach, the appropriateness of the proposal cannot be assessed.

Design approach

Just as there are many research approaches, there are also many ways to design these things. Again, it is possible to distinguish between the design and the methods used within the design process. For example, Design Thinking (Buchanan, 1992) can be seen as an overall approach to a design process within which many methods can be combined. Design methods in turn can be divided into types. Martin & Hanington (2012) list 100 design methods and distinguish between research methods, synthesis/analysis methods and research products. The CMD Research Methods Pack10 lists 58 of these and divides them by:

- library methods to uncover pre-existing knowledge;

- field methods to map user needs and requirements;

- laboratory methods to test whether a design works;

- showroom methods to have your design validated by the outside world;

- workshop methods to explore options;

- stepping stones to capture and communicate results to the team and the outside world (Van Turnhout et al., 2014).

There is overlap between design methods aimed at gathering information (such as library methods and field methods) and research methods. However, there is a difference in the use of these methods. Within the research approach, methods are used to help answer a research question. The quality of the response is primarily determined by looking at the data collection quality. Within the design approach, methods are used to help arrive at a design. The quality of the design is primarily determined by whether the design makes a valuable contribution to the practice issue. This means that research methods are generally subject to different requirements than comparable design methods.

Didactic approach

When a research project also aims to have people learn something – during or after the research project – an approach for this should be considered, i.e. a didactic approach. Within the CAYR methodology, the broad meaning of the term ‘learning’ given by Ruijters (2006, p.48) is used for this purpose: ‘Learning comes from the “zone of not knowing/the unknown” and, through a variety of physical and mental activities, leads to the discovery of understanding and competence.’ This involves all those events in which people don’t know something at first, then engage in activities (both thought and action) that lead to them having a better understanding and increased competence.

The developer of a research design is tasked with determining what physical and mental activities stakeholders need to do in order to learn. The most passive form of ‘encouraging learning’ goes no further than disseminating research findings and hoping that practitioners will learn from them by reading them. This turns out to be not very effective (Bero et al., 1998). Slightly more actively, teaching materials can be developed as part of a research project, incorporating the research results and when these teaching materials are included in a curriculum. In this way, future professionals can learn from the research findings. However, this also proves to be not very effective (Bero et al., 1998). More actively still, a research project may include the organisation of interactive meetings with professionals or incorporate the principle of audit and feedback (Lau et al., 2015). This has been found to be quite effective in many cases (Bero et al., 1998).

Notably when the research project itself is seen as an opportunity for stakeholders to learn something. Research projects can be very rich learning environments where participants can learn in five directions (Markauskaite & Goodyear, 2017, p.596):

- up: by linking practical experience to theory;

- inwards: by learning more about yourself as a person and professionalism;

- forwards: by developing new actionable knowledge for future action;

- sideways: by becoming more skilled in mutual cooperation, often across disciplines;

- downwards: by being grounded better thanks to an improved understanding of contextual constraints and own preferences and learning to improve your learning from everyday experiences.

This can be achieved by giving stakeholders in practice a role in the execution phase of the research project. In the Getting all stakeholders in position element on this website, ways in which this can be given form are discussed in detail.

The ‘CAYR as a complete 10-step process’ manual includes a complete workshop called ‘setting up cooperation’ on page 40. This workshop combines different working methods to support the participants in the partnership in jointly determining who will be involved in which research activity, in which roles and with which tasks and duties in the execution phase of the research project. The workshop is a half-day session and can be organised either online or on-site. The description of this workshop can give project leaders and process managers more insight into how the above-mentioned working methods and tools can be used (whether combined or not) and can serve as inspiration for how meetings can be organised from the basic principles of CAYR.

Change approach

Changing people is not an easy task. Yet the objective of practice-based research is often to contribute to that change beyond simply producing new knowledge, for example by changing something about the system or the people in it, and/or having people learn something, and/or creating something.

Changes can relate to the behaviour of individuals. The literature then talks about ‘behavioural change’. A well-known approach in healthcare for this purpose is the Behavioural Change Wheel (Michie, van Stralen, & West, 2011), a synthesis of 19 models for behavioural change. This model consists of nine types of interventions (such as training and persuasion) and seven policy strategies (such as communication and guidelines) that ensure that individuals want, can, and have the opportunity to change their behaviour.

Changes can also relate to the behaviour of groups. This may involve changing teams, departments, organisations, government policies or healthcare systems. This is a broad area of expertise involving numerous disciplines. In practice-based research, it is important to consider what role the research project plays or can play in these change processes. A passive role can be to ensure that key stakeholders within a system are involved in the study. Subsequently, the aim is that they will use the research findings for change in protocols, policies and ways of working. A more active role can be to actively help formulate policies and protocols within a research project.

It is wise to think about how the research promotes change early on, when developing a research approach. You can do this by developing a ’theory of change’ (Stein & Valters, 2012; Taplin & Rasic, 2012): a theory of the path by which research leads to change. The impact of research often runs along several paths termed ‘impact pathways’ (Springer-Heinze, Hartwich, Simon Henderson, Horton, & Minde, 2003). By identifying these impact pathways in the start-up phase of a research project, it becomes clear which activities can be included in the research project to increase its impact. It also helps to substantiate the relevance of the research project to the grant or subsidy provider.

Complex systems are resistant to change, but paper has patience (Vermaak, 2009). The most active way of using practice-based research to contribute to changes in practice is to include a change strategy as part of the research project. De Caluwe & Vermaak (1999) distinguish between five change strategies and assign each one its own colour:

- blueprint thinking is the rational planning strategy;

- yellowprint thinking is the interest strategy based on power and coalitions, among other things;

- redprint is the people-centred strategy focused on reward and punishment, among other things;

- greenprint is the growth-oriented strategy focused on learning and motivation, among other things;

- whiteprint is the energy-oriented strategy based on self-organisation and creativity, among other things.

The idea is that a change strategy should fit the practice issue and context. When developing a research approach, it is possible to consider which change strategy fits the practice issue and which activities can be included in the research project to realise this strategy.

Additional helpful resources

- Support in realising, and reporting on, the impact of research projects to universities of applied sciences: Impact of research in higher professional education – Support in improving the impact of research at universities of applied sciences (doorwerking-hbo-onderzoek.nl)

- For formulating and developing a change approach: De Caluwe, L., & Vermaak, H. (1999). Leren Veranderen. Een handboek voor de veranderkundige. Alphen aan den Rijn: Samsom.

- For more theory on Impact Pathways: Springer-Heinze, A., Hartwich, F., Simon Henderson, J., Horton, D., & Minde, I. (2003). Impact pathway analysis: An approach to strengthening the impact orientation of agricultural research. Agricultural Systems, 78(2), 267–285.

- For behavioural change theory: Michie, S., van Stralen, M. M., & West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6(1), 42.