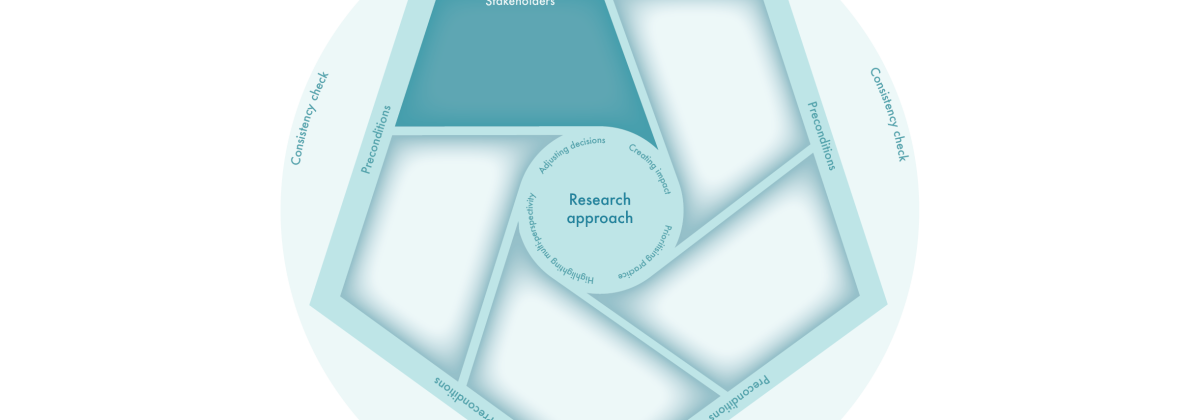

The knowledge, working methods and tools offered in this element can be used by researchers at their own discretion for one or more of the objectives below:

- gaining insight into who in practice are involved in a practice issue for which a practice-based research proposal is to be developed.

- getting stakeholders to specify why they want to contribute to the development of a practice-based research proposal around a specific theme

- jointly specifying and making choices about the roles and duties that stakeholders (will) have in a process of developing a practice-based research proposal

- gaining insight into what people need in order to be able to perform their duties and roles within the partnership well

- gaining insight into which people should be involved in the execution phase of the study, in what role and with what tasks.

Why put all those involved in a practice-based research project in position?

Developing practice-based research that really has an impact in practice is no simple task. Researchers often do not have the full picture when it comes to what is really going on in practice. Partners active in practice and experiential experts often have a better view on this, but conversely they usually know much less about how to methodically set up a study properly. In addition, support and commitment on location as well as the ability to respond flexibly to the situation there are necessary elements for research to have an impact in practice. Setting up such a study requires an interplay between researchers and stakeholders in practice. When considering stakeholders in practice, think of end-users such as citizens, clients, students, etc., as well as professionals, management, policymakers and many others involved in practice in a practice issue.

The knowledge clips below explain how the collaboration between researchers and practitioners can take shape in practice-based research, both in the preparatory and the implementation phases of the study.

The benefits of participation

Levels of participation

Equality between researchers and stakeholders in practice

For the interplay between researchers and stakeholders in practice to run smoothly, equality is key. This allows the different perspectives to be brought to the table, allows everyone to provide input in developing the research proposal, and creates co-ownership. In this, special attention is needed for the position of people with experiential knowledge. These are people who have experience in the project theme from their personal situations. This could include citizens, patients, children and their parents, young people, the elderly, people with disabilities, and so on. The CAYR methodology provides working methods that value all participants in a partnership and respect and address all different opinions on the practice issue, the objectives to be attained, and the research project. Mutual respect and creating a sense of belonging is important in this regard.

Forging a good partnership requires a lot of preliminary work

It is important for project leaders to have sufficient insight into who in practice are involved in the practice issue and who should be involved in developing a practice-based research proposal aimed at tackling this issue. This means they need knowledge of the different actors involved in the issue as well as their interests and positions (of power).

Tips for project leaders and process managers

The tips below are helpful in engaging all the different stakeholders and in keeping them engaged.

- Assemble the project group carefully.

-

- See which stakeholders are relevant to the practice issue. For this, perform a stakeholder analysis and involve people who know the practice from the inside who will also be able to play key-roles in the executive phase of the research. This will prevent that new people have to get involved who will see themselves as executers in stead of co-owners of the research.

-

- Select one or more participants for each stakeholder group. When doing so, carefully consider whether it is necessary to involve people who have experience in research, can think across boundaries, have multiple perspectives and/or enjoy (broad) support, or not. Explain why such a choice is made. Also ask people involved about who the decision-makers are in the context in which the future study will be conducted. This can also be done at a later stage if at the beginning of the process it is not yet clear in which context the study will be conducted.

-

- Ensure different types of expertise and perspectives are incorporated

-

-

- Prior to the partnership, discuss the ultimate objective associated with the practice issue very explicitly with each potential participant and have them articulate how and why they endorse this ultimate objective. The ultimate objective may still be formulated in abstract terms, such as ‘properly enabling elderly people to live at home longer’ or ‘more sustainable use of energy in deprived districts’.

-

-

-

- In this, also consider the stakeholders who are part of the system of which the practice context is part, e.g. municipalities and/or governments, health insurers, interest groups or (SME) companies.

-

-

- Identify opportunities and skills for working online, if applicable.

-

- Take stock of each (potential) participant’s prior knowledge in the field of the practice issue so that you can always ensure that everyone is enabled to contribute to the development of the research proposal during each exchange.

-

- Let people with experiential knowledge meet beforehand so that they can support each other in the process of developing a research proposal. You could organise a joint informal meeting with all participants beforehand. This enhances the working atmosphere.

-

- Creating equality and connecting with each other often leads to a positive working atmosphere. Make sure this does not lead to people not daring to speak up critically. Regularly invite people explicitly to play devil’s advocate and to use their experience and knowledge to account for the familiar bumps and recalcitrance of practice in the research plan.

- Customise workshops

-

- Customise the workshops appropriately, in light of the circumstances. Make them shorter when participants have a lesser workload capacity. Avoid using break-out rooms in online sessions if participants are not very IT-proficient.

Prior to each collaborative session, it is important for process managers to take note of what the individuals in the group need to participate. Consider, for example, the extent to which people are skilled in terms of reading, writing and research, what people need to be able to listen attentively or feel safe enough to contribute ideas in the group. Customise or adapt the setting and working methods accordingly. Is the working method in writing, and are not all participants able to bring this to a successful outcome? Then see if it is possible to replace writing by drawing, or use association cards instead of asking people to write or draw something from scratch themselves.

Helpful working methods

Choose the context

In this working method, the project group discusses the different contexts in which future research could take place. The background of everyone involved is considered in these different contexts.

To-Do list

Working method to jointly consider who can and wants to take on which duties and roles. This working method can be used for the process of jointly developing the research proposal and/or for the execution phase of the research project.

Weaving a network

Working method to jointly identify who wants to play what role in the execution phase of the research project and to identify dependencies.

Background information

Involving stakeholders in practice in research and researchers in practice (i.e. participation) is an important dimension in developing a research proposal. Such participation can enhance the quality and applicability of research (Brett et al., 2014). Often, however, the role of people with practical knowledge in research is limited to the level of consultation: discussing the research design and providing input and feedback during the research project.

However, it is also possible to involve people with practical knowledge such as citizens, patients, relatives, professionals, managers and administrators more actively in research as a form of co-production (INVOLVE, 2018) by giving them a role as researchers. Co-production goes beyond simply organising ‘productive interactions’ in consultation (ZonMw, 2018). Having stakeholders contribute their practical knowledge and experience as researchers is also an option and may be desirable. This can further enhance the validity and usability of the knowledge to be developed and at the same time, as researchers, they can learn new things, the research can contribute to changing their local context and support for further implementation may be created.

Stakeholders can participate in research projects at different levels. Baxter, Thorne, & Mitchell (2001) distinguish between passive, consultative, active, and ownership levels.

(Baxter et al., 2001). Different roles can be specified within these four levels. At the passive level, stakeholders only have a role in the research project as subjects and respondents. Consultations provide the opportunity for stakeholders to give their reaction to the research design or research findings, or they can be given a slightly more active role as advisers who advise the researchers on the research project, solicited and unsolicited.

Several variants are possible at the active level. Stakeholders can be used to gather data as researchers, they can assist in data analysis, or they can be members of the research team as full co-researchers. This level is also referred to as the level of ‘participatory research’. In their research on this matter, Jagosh et al. (2012) discovered that participatory research adds value through a number of mechanisms:

- Promoting context-appropriate research;

- Getting respondents, advisory bodies, and implementation staff available;

- Increasing competences among stakeholders and researchers, which contributes to the professionalisation objective;

- Creating productive conflict and subsequent negotiation, which contributes to the change objective;

- Contributing to greater quality of outcomes;

- Increasing the permanence of impact, which contributes to the change objective;

- Creating system changes and unexpected projects and activities.

At the level of ownership, stakeholders also have decision-making power and (co-)decide on the design, progress and completion of the research. At this level, this can also be called ‘user-controlled research’ and ‘empowerment’ (Hanley, 2005). Often, the choice of user-controlled research is made not only to promote the validity and impact of the study, but also based on ethical and idealistic considerations. At the level of ownership, there is complete equality between researcher and stakeholders and there are no differences in power.

Participation in practice-based research may include the participation of researchers in practice. Researchers may be invisible data collectors when using administrative data or when conducting document reviews, for example. They become visible as soon as they start interviewing or conducting surveys. They do enter the practice as observers, but in a passive role. When they start doing the same activities as stakeholders in practice, they become participants. This happens, for example, in participatory observation. The next level follows when researchers start actively intervening in practice as interventionists. This could be to test something out, as in an experiment, or with the aim of improving the local situation.

Such an intervention made as an interventionist is often one-off, but that changes at the next level of participation where the researcher participates in the local practice issue for a longer period of time. This can be done, for example, in the role of coach, which is common in action research (Pluut, 2018). Stakeholders then conduct their own research on how to improve their situation, guided by a researcher. The researcher can also take on the role of change agent who initiates change himself. At the highest level, the roles of researcher and stakeholder completely overlap. This is the case of practice-based research where, for example, healthcare professionals themselves fully design and conduct the research project, without the involvement of an external researcher.

Additional material

– The co-design canvas is a tool developed by Wina Smeenk, Anja Köppchen and Gène Bertrand (2020) to start, plan, execute, and evaluate collaborations around societal challenges with different stakeholders in an open and transparent way. It maps differences in interests, knowledge, experience and power relations, considers the desired positive impact and concrete results from the start, and ensures everyone’s voice is heard: Het Co-Design canvas 2023 (Dutch) (inholland.nl)

– The participation matrix developed by Smits, Van Meeteren, Klem, Alsem and Ketelaar (2020) from UMC Utrecht is helpful in mapping stakeholders and their role in the project: Participatiematrix (kcrutrecht.nl)

– Pharos has a website with helpful working methods, research methods and information to encourage engagement: Samen bereiken en betrekken om Gezondheidsverschillen te verkleinen – Pharos